From Classics to Museum Studies: the journey of Lucrezia Gigante

Lucrezia Gigante welcomed me with a nice cup of coffee — made the Italian way with a moka pot. Although she has been living in England for some time now, this ritual remains an essential part of her daily life. Currently, she’s a research associate at the University of Glasgow, but her path to reach this point hasn’t been exactly linear.

She first studied Classics in Milan, but soon realized she didn’t want to teach Latin, Greek, or Italian. Instead, she was drawn to museums. But how do you work in a museum when you haven’t yet acquired any formal training in this field? That was the question haunting her as she completed her degree.

So, she did what many of us would do — she googled “museum + studies.” And there it was: a full academic program in Museum Studies at the University of Leicester in the UK — actually the first of its kind. She felt drawn to it by its multidisciplinary and socially-engaged qualities, which she knew aligned well with her own values.

I find the backstory of this finding so interesting because this happened while she was walking a stretch of the Camino de Santiago with her sister. So, as fellow travellers asked about her future academic plans, she answered, “I’m going to study Museum Studies in Leicester.” And the more she said it, the more real it became as if speaking it aloud helped her believe it was truly possible.

The Master’s degree turned out to be more than she expected. It opened her eyes to new possibilities — not ones imposed by others, but ones she defined for herself. She felt empowered, supported, and, most importantly, that her ideas mattered. She explored how museums could foster horizontal exchanges with society — moving beyond the traditional top-down model of education where museums are seen as sole holders of knowledge. This period of her life, she says, ignited the “sacred flame of research,” and she recalls it with tears of gratitude.

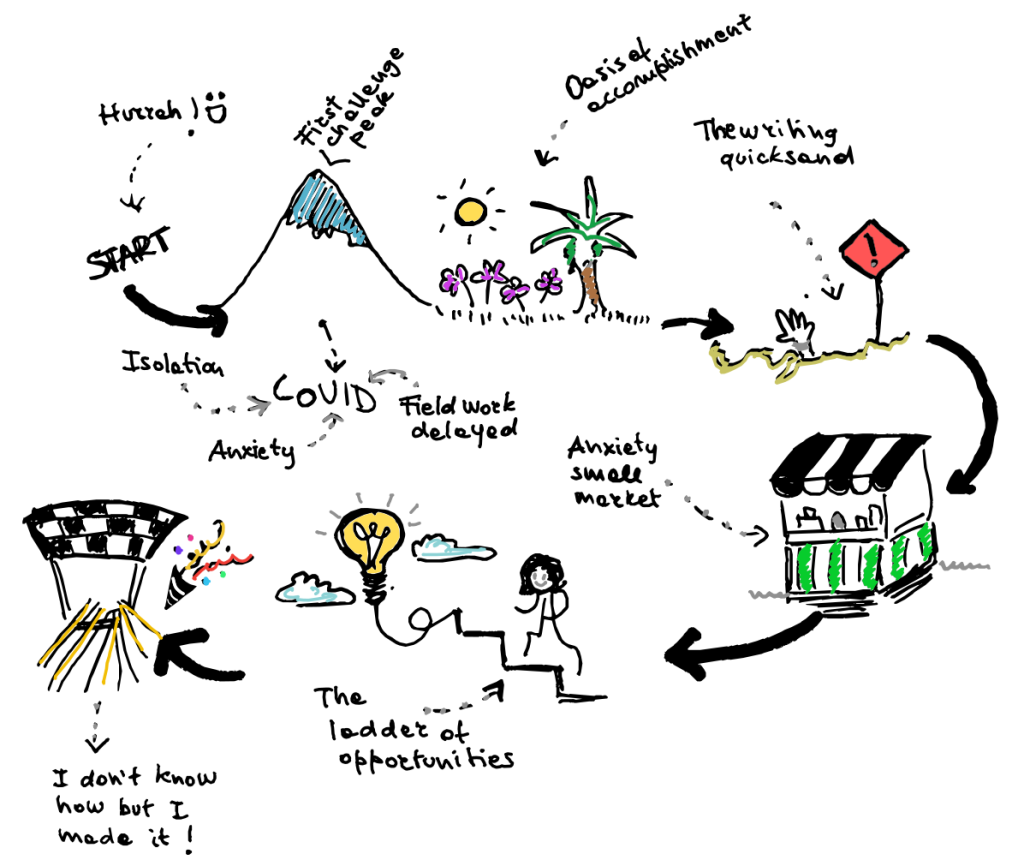

At the end of the Master’s, she applied for a PhD and September 2019 marked the beginning of this new adventure. The first months were surprisingly fun — so much so that a friend asked if she was “doing it right.” In the UK, the first year of a PhD is dedicated to literature review and shaping your research direction. Lucrezia enjoyed very much this exploratory phase and her supervisors gave her room to grow.

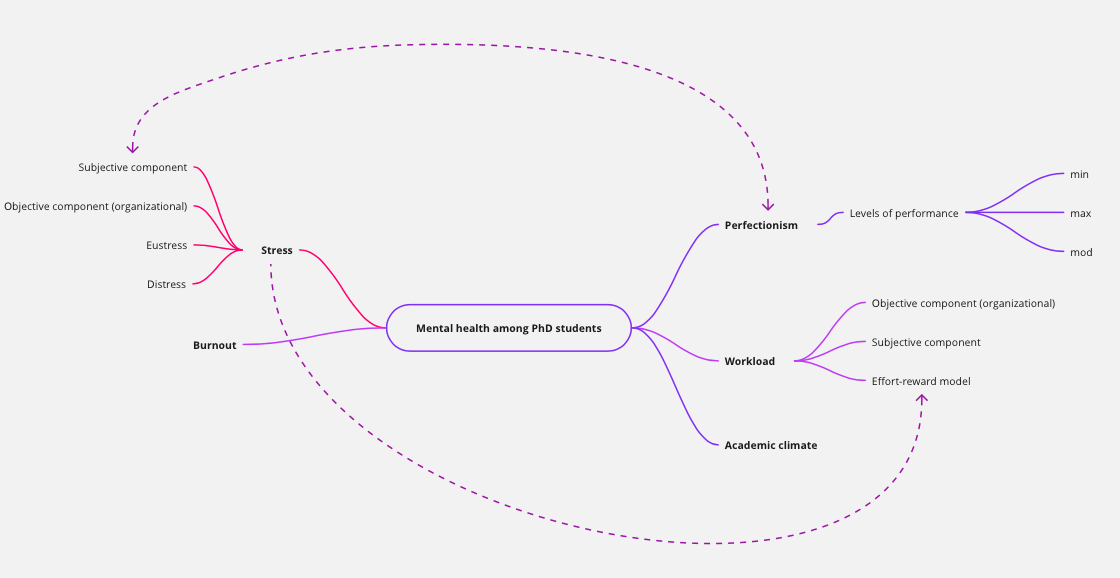

Then came COVID. The pandemic brought both personal and professional challenges. As many of us experienced, being far from her family was difficult, and academically, the isolation was day by day more real, since conferences were canceled and museums shut down. This was of course a big blow to her planned fieldwork. One of her supervisors, at this point, also suggested she shift her focus to digital humanities.

But Lucrezia remained true to her original vision and that persistence paid off because, with museums worldwide closed to visitors, professionals were more available for remote interviews. She went from working with three envisioned museums in the UK to conducting twenty-two interviews with ten art institutions around the globe! This was a real success!

However, soon after, came the next hurdle: writing under pressure. She had mountains of data but little time because her PhD contract was quickly running out. And suddenly, 80,000 words, which is the UK standard for a PhD thesis, didn’t seem enough. “Will I make it?” she asked herself, over and over again.

Naturally, the first thing she did was talk to other PhD students. After all, who else truly understands the joy of formatting footnotes at 2 a.m.? But as comforting as it was to talk about each others worries, it didn’t always help. The thing is that when everyone around you is stressed too, it can start to feel like a little town market, where everyone is trading their anxieties like collectibles, but no one is really sure how to help. However, Lucrezia explored also a new path by joining a coaching program that helped her regain clarity and control over her writing process.

At the same time, she also stayed engaged in academic life beyond her research. For instance, she served as a PhD representative, organized seminars and writing sessions (famously known as shut up and write), worked as a teaching assistant, and even served as editor-in-chief of the PhD-led Museological Review journal.

This is the concept of the so called “non-places” to which I was introduced by Giovanna (IG @anemaestorie).

To all aspiring or enrolled PhD students, Lucrezia advices to

- Don’t be afraid to change the course of your studies if at some point you don’t feel they reflect who you have become. She went from Classics to Museum Studies, and it wasn’t a painful turn of direction, as long as you stay true to yourself.

- Choose your supervisor carefully — as a person.

Spend time with them, even just an hour, to understand their personality. A PhD takes years, so the human connection matters. - Redefine what “prestige” means.

A prestigious university is one that supports your growth — through training, a strong research culture, and real postdoc opportunities — not just big names on your papers or your future CV. - Take opportunities beyond your thesis.

Extracurricular experiences are valuable. The PhD will end — it’s good to have doors open when it does. - Learning what you don’t like is also part of the journey.

It helps shape your future direction just as much as discovering what you love. - Invest in a good screen.

It may sound trivial, but if you’re writing thousands of words, your eyes, neck, and sanity will thank you.

At the end of this story, Lucrezia reminded me that the academic journey might also not be a straight line — but with clarity of purpose, courage to stay true to yourself, and a good moka coffee 😉 , it can be deeply transformative.

Lucrezia has a wonderful and coloured website to get to know her and be in touch: https://www.lucreziagigante.com/.