Why Sharing #ResearchGoodsBads Matters: Insights from Evelyne Fraats

I was scrolling through LinkedIn when I stumbled upon a refreshingly honest post about research setbacks and small victories and I thought that, in a sea of self-celebratory updates, this felt like a breath of fresh air. The writer, Evelyne Fraats, is a second-year PhD candidate in social and moral neuroscience at Ghent University. Her research focuses on how our brains process moral and social decisions, and on LinkedIn, next to outreach work, she launched the hashtag #ResearchGoodsBads, where she shares candid reflections on PhD life.

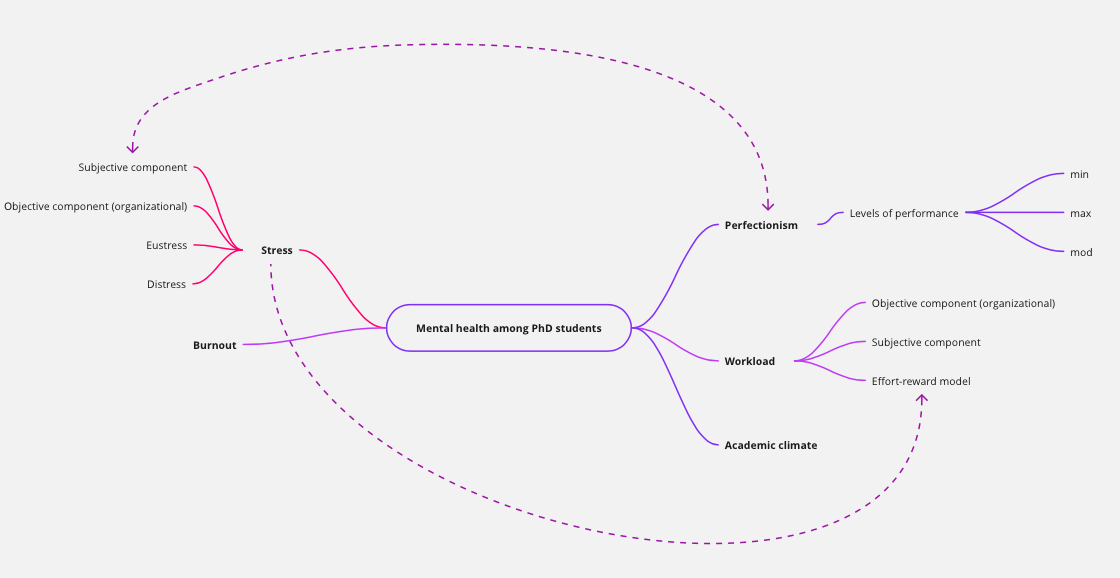

Evelyne’s PhD is part of a larger project at Ghent University investigating what happens in our brains when we face moral choices. One study1 from her supervisor’s lab, for example, found that when people followed orders to hurt someone, the brain’s usual “conflict signal” was much quieter than when they made the same choice voluntarily. In other words, obedience seemed to mute that inner alarm that normally contributes to our aversion to hurt people.

For Evelyne, working in this field means not only running experiments and analyzing EEG data (which refer to the brain’s electrical activity) but also thinking deeply about what these findings reveal about human responsibility. “It makes you very aware of what is going on around you,” she told me. I must add, in times like these, that feels especially relevant. Another reason she enjoys her topic is its immediate social relevance: people instantly understand what she studies and are eager to talk about it. “Science is not finished until it is communicated,” she said. That belief drives her passion for science communication. Beyond publishing papers, she writes for Dutch platforms, contributes to newsletters in Belgium, and even organises the BrainQuiz Festival in the Netherlands.

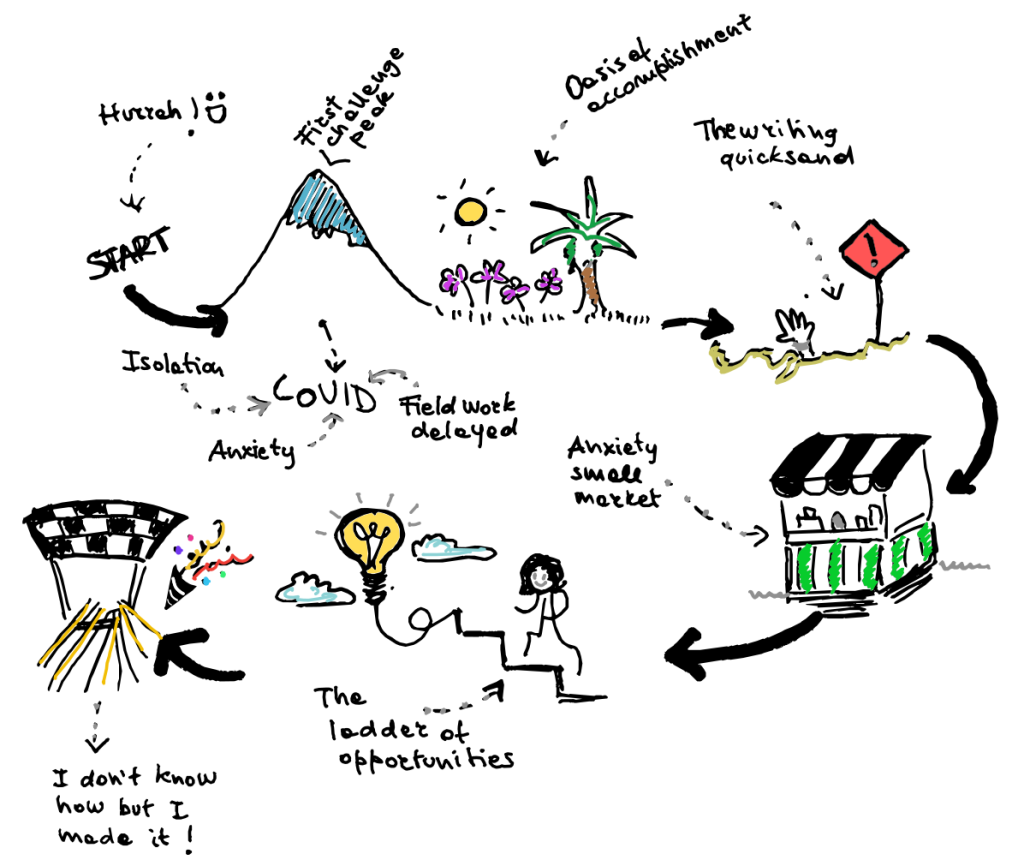

However, reaching her current position wasn’t straightforward. She had to navigate several rejections before securing her PhD. “How do you stay motivated when things don’t go the way you wish?” I asked. She admitted that the rejection letters hit her hard at first. She felt deeply disappointed. But with time, she learned to reframe them (often with sarcasm), finding some positive meaning in them. Being open and vulnerable about it on platforms like LinkedIn helped her to feel supported and added a sense of realism to a common situation.

In truth, she simply really wanted to do a PhD! It felt like the natural next step. During her master, she loved the flexibility, the process of designing experiments, working with data, reading and writing about science. As she put it, “I like searching for the truth.”

Her early challenges during the PhD had less to do with academic work and more with the administrative side of ethical studies involving human participants. Convincing an ethics committee takes much more than she had anticipated, especially when doing sensitive work in the field of moral decision. As a result, her entire timeline shifted. She had imagined she would have completed her first study and written a paper by now. After the initial frustration, she adjusted her expectations and learned to be okay with where she was.

Because she is so immersed in her project, I asked her whether she ever feels lonely in her research. “It depends!” she said. “In the lab, maybe yes, but in the office, no.” I think what she means is that she can feel lonely at times, but never alone. She feels supported both technically and personally by her colleagues and her supervisors.

Speaking of her supervisors: although she knew almost nothing about them before starting, beyond what she found on their LinkedIn profiles, she has come to appreciate their strong guidance and speaks very highly of them.

Last but certainly not least, her advice to fellow PhD students is to acknowledge that there will be both good and bad moments during the PhD journey, so better to be open about them, and share the insecurities with friends or also with your LinkedIn network! The latter might sound scary, to be real and authentic on a networking social media platform, but Evelyne’s experience clearly shows that when this platform is used with honesty, rather than performance, it can become a space for connection instead of comparison.

And… “the coffee from the university machines is not too bad,” she added with a smile, which makes her colleagues laugh a bit because they hate the coffee from the machine.

I became a big fan of her hashtag #ResearchGoodsBads, even if I’m still skeptical about the coffee suggestion! Above all, I became a fan of her insistence that we don’t have to pretend our PhD journey is smoother than it is.

If more of us shared the real story, maybe we’d discover we’re not as alone as we think.

1 Caspar, E. A., & Pech, G. P. (2024). Obedience to authority reduces cognitive conflict before an action. Social Neuroscience, 19(2), 94–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470919.2024.2376049

Extra reading if you enjoy this topic: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/authenticity-digital-media-importance-aligning-real-world-caity-begg/